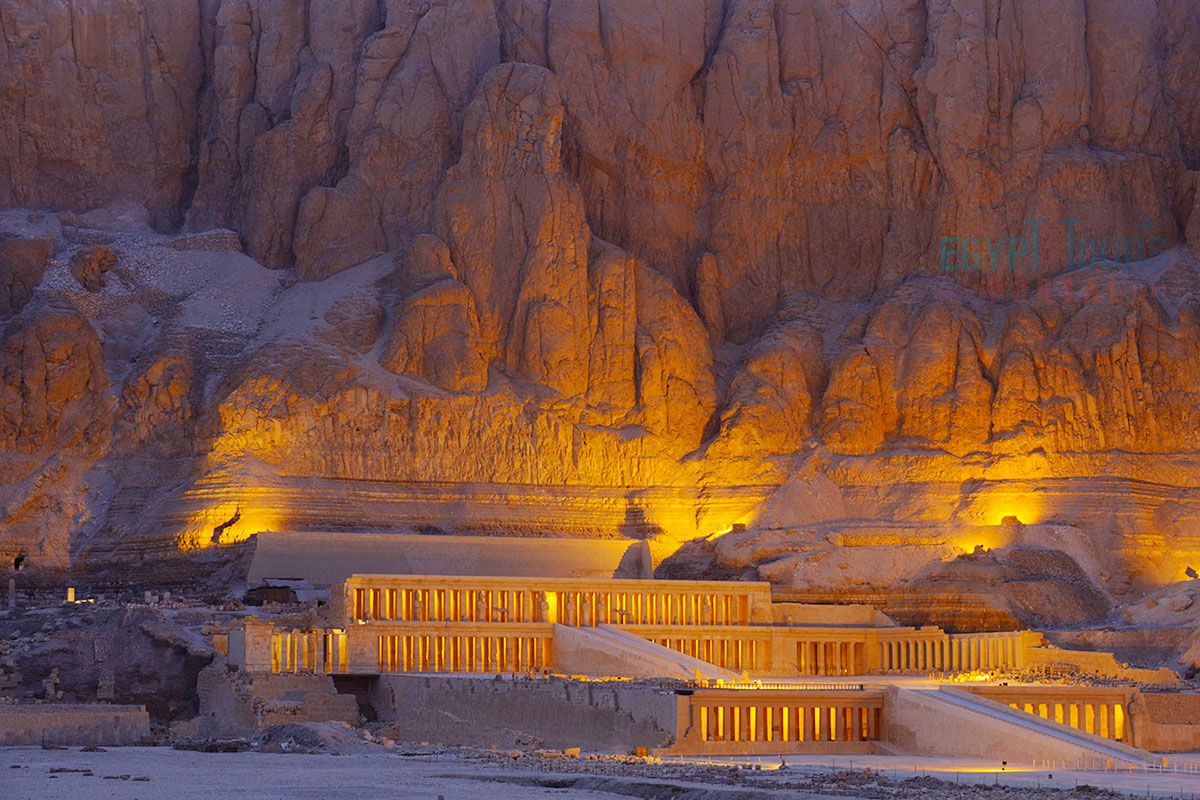

The Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari is a stunning architectural masterpiece built for Egypt’s renowned female pharaoh. Located near Luxor, it features three grand terraces adorned with reliefs depicting her divine birth, trade with Punt, and worship of gods like Amun and Hathor. Designed by Senenmut, the temple harmoniously blends with its cliffside setting. Though later damaged, modern restoration has preserved its legacy, standing today as a tribute to Hatshepsut’s power, vision, and groundbreaking reign.

The Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari stands out as one of the most breathtaking living miracles of the architectural and cultural achievements of ancient Egypt. This iconic mortuary temple, built for one of history’s few and most celebrated female ancient Egyptian pharaohs, embodies the grandeur, precision, and creativity that defined the civilization of the Nile.

The Temple of Hatshepsut remains a crowning jewel in Luxor’s collection of sacred sites, drawing visitors from around the world who come to marvel at its beauty and reflect on the remarkable legacy of the "female king" who left an indelible mark on Egyptian history. Hatshepsut’s temple is an architectural marvel and a powerful symbol of her remarkable reign, during which she defied convention to rule as king.

The temple’s grand terraces, intricate reliefs, and harmoniously designed layout reflect the artistic brilliance of the Eighteenth Dynasty and highlight the vision and strength of Hatshepsut, remembered as one of Egypt’s greatest rulers. This magnificent structure, with its elaborate colonnades and detailed carvings, showcases the pinnacle of skill in ancient Egyptian architecture. It offers modern visitors a glimpse into the power, reverence for the ancient Egyptian gods, and the legacy of a queen who sought to immortalize her name.

The breathtaking Temple of Hatshepsut, also known as "Djeser-Djeseru" or the "Holy of Holies," stands as a magnificent tribute to the Eighteenth Dynasty’s unique Pharaoh-Queen Hatshepsut. This architectural wonder is one of ancient Egypt’s most distinguished achievements, celebrated for its exceptional design and dedication to the creator god Amun and the enduring legacy of Hatshepsut herself.

In the tradition of Egyptian monarchs, it was the duty of rulers to construct monumental structures that honored the gods and preserved their legacy through eternity. Hatshepsut’s ambitious vision for her mortuary temple served both to elevate her public image as a divine ruler and to ensure her name would be remembered for generations.

Seen as the daughter of the powerful god Amun, she ruled for nearly two decades, choosing to adopt a male image and title as “pharaoh” to assert her authority in a society that traditionally reserved such positions exclusively for men.

Queen Hatshepsut (1507–1458 BC), the daughter of King Thutmose I and his queen Ahmose, inherited a remarkable lineage. Her father, King Thutmose I, also had a son, Thutmose II, from a secondary marriage with Mutnofret. In line with royal tradition, Hatshepsut married her half-brother Thutmose II before she reached her twenties, a union that elevated her status further.

Eventually, she attained the prestigious title of “God’s Wife of Amun,” the highest honor a woman could hold after becoming queen, granting her significant political influence and reverence. Following the early death of her husband, who left behind a young son, Thutmose III, Hatshepsut assumed control as regent and managed the affairs of state with strength and vision. In the seventh year of her regency, she broke with tradition and declared herself Pharaoh of Egypt, a position that she would hold with distinction.

Her reign is remembered as one of Egypt's most prosperous and stable periods, characterized by flourishing trade, a booming economy, great diplomatic relationships with neighboring countries, and a series of public works projects that provided widespread employment across the nation, embodying the ancient ideal of ma’at, or cosmic balance.

Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple is situated in the Upper Egyptian region of Deir el-Bahari, located below the rugged cliffs of the Theban Necropolis. The name “Deir el-Bahari” derives from the Coptic monastery that was established on the site centuries later. It is found about 17 miles northwest of modern-day Luxor, the temple stands on the west bank of the Nile river, near what was once Egypt's grand capital of Thebes during the New Kingdom of Egypt (1550-1050 BCE).

Its strategic location places it adjacent to the older mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II, marking the symbolic entrance to the famed Valley of the Kings, a nearby necropolis that you can explore on an extended Egypt tour. This specific site was chosen to connect Hatshepsut with the legendary Mentuhotep II, who had been highly venerated as a ‘second Menes’ for reuniting Egypt and founding the Middle Kingdom.

The history of the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari is intertwined with the life and reign of one of ancient Egypt’s most remarkable rulers. Hatshepsut, who ruled from around 1479 to 1458 BCE, was the daughter of Thutmose I and became the wife of her half-brother Thutmose II. When Thutmose II died, leaving his young son Thutmose III as his heir, Hatshepsut initially served as regent.

However, in a bold and unprecedented move, she eventually declared herself Pharaoh, assuming the full title and regalia of a king. This unique position required her to establish her legitimacy and authority, not just as a queen, but as a reigning pharaoh, which was a role traditionally reserved for men.

To do so, Hatshepsut undertook ambitious building projects across Egypt, the grandest of which was her mortuary temple, a testament to her vision, her divine claim to rule, and her desire to be immortalized in the Egyptian tradition of monumental architecture.

It was constructed around 1479 BCE, The temple was designed by Hatshepsut’s trusted architect and close advisor, Senenmut. It was inspired by the neighboring mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II, the Middle Kingdom pharaoh who unified Egypt. Still, Hatshepsut’s temple was designed on a larger, more elaborate scale, signaling her desire not only to link herself with past glories but to surpass them.

The temple’s placement beneath the towering cliffs of Deir el-Bahari was no accident; it was a setting chosen to blend the natural landscape with human-made architecture, symbolizing Hatshepsut’s connection to both the gods and the natural world.

One of the temple’s main historical purposes was to serve as a site for Hatshepsut’s own mortuary cult and for annual ceremonies honoring the god Amun. During the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, the barque of Amun was carried from Karnak to Hatshepsut’s temple, where offerings were made to honor both the god and the queen. This festival reinforced her divine connection to Amun and highlighted her status as his earthly representative, legitimizing her position in the eyes of her people.

The temple’s three grand terraces and intricate reliefs also played a key role in establishing Hatshepsut’s narrative of divine legitimacy. On the walls of the temple’s second terrace, carvings depict scenes of her divine birth, wherein Amun takes on the appearance of Hatshepsut’s earthly father, Thutmose I, to conceive her, thus establishing her as a semi-divine figure.

Another significant historical depiction is the famous Punt Colonnade, illustrating Hatshepsut’s successful ancient Egyptian trade expedition to the fabled land of Punt. This accomplishment brought exotic goods, incense, and wealth to Egypt, reinforcing her reputation as a capable and prosperous ruler.

However, Hatshepsut’s story took a darker turn after her death. Her successor, Thutmose III, eventually ordered the erasure of Hatshepsut’s name and image from public monuments, an effort to eliminate her legacy from historical memory. He ordered that her images in the temple be defaced, and her statues were smashed and buried.

Historians believe this act may have been intended to restore traditional male succession and discourage other ancient Egyptian women from claiming the throne. Later, during the Amarna Period, Akhenaten’s reforms targeted the worship of Amun, further damaging parts of the temple.

Despite these attempts at erasure, Hatshepsut’s temple endured. Archaeologists from the 19th century onward uncovered and restored much of the site, revealing the stories that Hatshepsut had worked so hard to preserve. Since 1961, the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission has worked to restore and protect the temple, unveiling more details about Hatshepsut’s reign and architectural ingenuity.

Today, her temple at Deir el-Bahari stands as one of Egypt’s most iconic monuments, embodying the historical impact of a ruler who defied convention and left an indelible mark on Egypt’s legacy.

Explore the marvelous temples of the ancient Egyptian civilization

Read More

The architecture of Queen Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahari is a remarkable achievement that blends monumental scale with harmonious design. Known as Djeser-Djeseru, or “Holy of Holies,” the temple stands as a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian architectural innovation, designed by Hatshepsut’s trusted architect Senenmut.

Inspired by the nearby Temple of Mentuhotep II, Hatshepsut’s temple takes that original design to a grander scale, creating a unique structure that integrates seamlessly with the natural cliffs that rise dramatically behind it. This layout and placement served both symbolic and practical purposes, linking Hatshepsut’s temple with both divine presence and the eternal landscape.

The temple’s layout consists of three massive terraces that rise in ascending order, connected by broad ramps leading from one level to the next. Each terrace represents a distinct architectural style and purpose, showcasing both Hatshepsut’s accomplishments and her divine legitimacy.

The terraces are lined with rows of impressive columns and porticoes, each adorned with intricate reliefs, statues, and inscriptions that narrate key events from Hatshepsut’s life and her connection to the gods. The entire temple was built primarily from limestone, with some sections of sandstone and red granite brought from distant quarries, a testament to the logistical skills and resources of her administration. Here are the incredible architectural elements that shape this magnificent monument:

Explore the marvelous architecture of the ancient Egyptian civilization

Read MoreThe first terrace, or Lower Terrace, is reached by a grand causeway that once led from the Valley Temple to the temple’s entrance. This terrace is enclosed by a wall and once featured lush gardens with exotic trees brought back from Hatshepsut’s famous expedition to Punt. Behind the courtyard lies a row of colonnades, their square columns designed to introduce visitors to the temple’s immense scale. Decorative reliefs on the lower terrace depict scenes from nature and offer glimpses into the flora and fauna of the Nile region.

The Middle Terrace is perhaps the most famous and richly decorated of the three levels. A wide central ramp leads to this terrace, where two reflecting pools and rows of sphinxes once lined the path, adding to the temple’s grandeur. Here, the Birth Colonnade and the Punt Colonnade are located on either side of the central ramp.

The Birth Colonnade narrates the story of Hatshepsut’s divine birth, detailing how the god Amun took the form of Thutmose I to conceive her, establishing her divine right to rule. The Punt Colonnade illustrates her ambitious trade expedition to Punt, depicting the goods, animals, and exotic items brought back to Egypt and reflecting her reign’s prosperity and connections to distant lands.

On this terrace, two chapels dedicated to the deities Hathor and Anubis are also featured. The Hathor Chapel includes columns with Hathor-headed capitals, portraying the goddess with a woman’s face and cow’s ears, a design unique to this region and associated with femininity, fertility, and beauty. The Anubis Chapel, dedicated to the god of mummification and the afterlife, is located at the northern end, decorated with vibrant colors and symbols that emphasize protection and passage into the afterlife.

The Upper Terrace, which represents the sacred heart of the temple, features a portico with double rows of towering Osiride columns, each depicting Hatshepsut as Osiris, god of the afterlife, with crossed arms holding the crook and flail. These columns emphasize her aspiration for eternal life and her association with divine kingship.

The Upper Terrace is accessible via a final central ramp and leads to the most sacred area of the temple, the Sanctuary of Amun. It was carved directly into the cliff, and the sanctuary serves as the culmination of the temple’s east-west alignment, symbolically linking Hatshepsut to the divine realm.

Inside the sanctuary, reliefs show Hatshepsut presenting offerings to Amun, affirming her dedication to the god. This area was later altered during the Ptolemaic period, with the addition of statues and structural changes that reflected changing religious practices. The upper terrace contains two chapels dedicated to the Solar Cult and the Royal Cult, both elaborately decorated with scenes of the royal family making offerings to the gods and honoring Hatshepsut’s legacy.

Hatshepsut commissioned the construction of her temple around 1479 BCE, a monumental task that took approximately fifteen years to complete. Her trusted architect and advisor, Senenmut, designed the structure, drawing inspiration from the neighboring Temple of Mentuhotep II. However, Hatshepsut’s temple was conceived on a grander scale, with larger dimensions and more elaborate features than any previous monument.

The temple is constructed on three ascending terraces, each offering a different experience of grandeur and architectural mastery. At the Ground Level, visitors would have passed through lush gardens filled with exotic trees that Hatshepsut brought back from her famous expedition to Punt, although these gardens have not survived.

The courtyard behind featured colonnades adorned with square pillars and decorative reliefs, including images of Thutmose III before Amun and depictions of Lower Egyptian marsh scenes. From here, a grand archway leads to the second level.

The Second Level of the temple features two reflecting pools and an avenue lined with sphinxes that lead visitors up a ramp, continuing the journey through Hatshepsut’s life and accomplishments. This level is remarkable for its artistic reliefs, including the Birth Colonnade, which recounts Hatshepsut’s divine birth as the daughter of Amun, and the Punt Colonnade, detailing her successful trade expedition to the legendary “Land of the Gods.”

The Punt Colonnade is especially fascinating, illustrating the diverse goods brought back to Egypt, including incense trees, exotic animals, and valuable resins. Additionally, the level houses two chapels dedicated to the gods Hathor and Anubis, each designed with distinctive columns and artwork reflecting the deep religious significance of the temple.

The Third Level, the highest terrace, reveals a stately portico with rows of tall columns, many of which once displayed statues of Hatshepsut. Although many of her images were destroyed or replaced by those of Thutmose III, this area still hints at its original grandeur.

The Sanctuary of Amun, lying behind the courtyard, is one of the temple’s most sacred spaces. This chamber was hewn directly into the cliff, connecting the queen symbolically to the earth and the gods. Later, during the Ptolemaic period, this sanctuary was restructured and dedicated anew to Imhotep, the famed architect and healer of ancient Egypt, further enhancing its historical legacy.

The primary purpose of the Temple of Hatshepsut was to serve as a site of worship, commemorating the queen’s life and immortalizing her as a godly figure. It was also meant to honor Amun, the king of the gods, as well as other prominent deities, such as Hathor and Anubis. Additionally, the temple played a crucial role in the annual Beautiful Festival of the Valley, a sacred event in which the barque of Amun was carried from the Temple of Karnak across the Nile and into Thebes’ western necropolis.

This ancient Egyptian festival, dedicated to remembering and honoring the deceased, saw offerings and celebrations within the temple as the god Amun’s barque was brought to the sanctuary. Thus, the temple’s layout was intentionally aligned to welcome the divine barque and celebrate Hatshepsut’s status among the gods.

The temple functioned as a mortuary site where offerings were made to the spirit of the deceased queen, thereby ensuring her presence in the afterlife. The structure’s detailed reliefs illustrate her achievements and divine heritage, allowing Hatshepsut’s image and accomplishments to endure beyond her lifetime, which would also serve to inspire future generations.

The columns at the Temple of Hatshepsut are notable not only for their sheer size and symmetry but also for the artistry and symbolism they convey. Each of the three terraces features rows of columns that vary in design depending on their location and purpose. The lower terrace contains square, box-like columns that introduce visitors to the temple’s grand scale.

Moving up to the second terrace, the colonnade includes more detailed columns, many of which are decorated with reliefs depicting scenes of Hatshepsut’s divine birth and her famous expedition to Punt.

One of the most distinct features on the second terrace is the Hathor columns in the Hathor Chapel. These columns feature the goddess Hathor with her characteristic face and cow’s ears, symbolizing fertility, beauty, and motherhood, virtues Hatshepsut sought to embody in her rule.

The upper terrace is lined with rows of Osiride columns, which show Hatshepsut as the god Osiris, with crossed arms holding a scepter and flail, emphasizing her role as a ruler bound for eternity. The columns were not only functional in supporting the grand structure but also held deep symbolic meaning, communicating Hatshepsut’s divine authority and immortal status.

The carvings within Hatshepsut’s temple are a testament to the artistic and narrative skill of ancient Egyptian artisans. Across the temple’s walls and colonnades, intricate carvings depict key events from Hatshepsut’s reign, such as her divine birth, which emphasized her legitimacy as a ruler through her claim as the daughter of the god Amun, and her ambitious trade mission to the Land of Punt.

The Punt Colonnade on the second terrace presents a vivid depiction of this voyage, showing detailed images of Punt’s inhabitants, flora, and exotic treasures brought back to Egypt, including myrrh trees, incense, gold, and exotic animals. These scenes were revolutionary as they showcased one of the first known instances of international trade depicted in monumental art.

In addition to these narrative carvings, the temple walls also feature elaborate religious and ceremonial scenes, including offerings to Amun and other deities. Many of the carved images reflect Hatshepsut’s efforts to project her image as both a legitimate and divinely favored ruler. Sadly, some carvings were defaced or altered by her successor Thutmose III, who sought to erase her legacy, but enough have survived to convey the grandeur of her reign.

Over the centuries, Hatshepsut’s temple suffered from natural decay, vandalism, and targeted destruction, particularly during the reign of Thutmose III, who ordered the erasure of Hatshepsut’s images and inscriptions. Later, during the Amarna Period, the temple’s Amun-related images and ancient Egyptian symbols were further damaged due to the religious reforms of Akhenaten.

By the 20th century, the temple was in a state of significant disrepair, requiring extensive restoration. Modern restoration efforts began in the early 1900s with teams from the Egypt Exploration Society and later the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These projects laid the foundation for further work in the latter half of the century. Since 1961, the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Expedition has undertaken major restoration efforts, including the reconstruction of terraces, columns, and detailed reliefs.

This ongoing work has transformed the temple, making it accessible to the public and revealing more about Hatshepsut’s extraordinary contributions to ancient Egyptian culture. Today, visitors to the site can admire its restored grandeur, gaining insight into one of ancient Egypt’s most remarkable female pharaohs and her lasting architectural legacy.

The Temple of Hatshepsut is celebrated not only for its innovative architecture but also for its perfect symmetry, a defining characteristic of ancient Egyptian design, which symbolized harmony and balance, central values in Egyptian culture. The temple not only honors Hatshepsut herself but also serves as a sanctuary for the gods she revered, linking her to the divine and ensuring her presence in the afterlife.

The temple’s design and layout would inspire many subsequent New Kingdom temples, with elements of its structure and symbolism replicated throughout ancient Egypt’s sacred architecture. Its seamless integration into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari is a powerful statement on the connection between the queen, the natural world, and the gods.

Furthermore, the temple’s reliefs and iconography emphasize Hatshepsut’s role as both a political and divine figure, asserting her authority in a male-dominated role through a unique blend of tradition and innovation. The architecture of Hatshepsut’s temple influenced subsequent New Kingdom mortuary temples and has continued to inspire modern architectural thought.

Its majestic terraces, graceful columns, and powerful reliefs make the Temple of Hatshepsut one of Egypt’s most important and enduring architectural achievements, offering a lasting glimpse into the life and ambitions of one of Egypt’s most extraordinary rulers.

Despite the challenges of time and occasional vandalism, the Temple of Hatshepsut remains one of Egypt’s most well-preserved monuments, captivating visitors from all over the world. Many travelers on Egypt tour packages note that the temple’s striking terraces, sophisticated reliefs, and significant historic role make it an essential stop.

This extraordinary temple, with its three massive terraces connected by sweeping ramps, is open to visitors daily from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. Outside the temple, a bustling bazaar offers a variety of souvenirs, adding to the site’s charm. Inside, guests can explore the iconic Birth Colonnade and Punt Colonnade, marvel at the chapels dedicated to Hathor and Anubis, and experience the spiritual depth of the Sanctuary of Amun, making it a journey through both history and architectural splendor.

While in Egypt, Everyone will have to visit the unforgettable Hatshepsut Temple, where the essence of royal beauty and the brilliant architecture of the golden day of the ancient Egyptian empire collide in the most magical fashion. Through our marvelous Egypt tours and an epic Nile River cruise, everyone will come to spend the most incredible travel experience among some of the most magnificent monuments ever made in existence.

Day Trip from Luxor to Cairo by Plane For Indian Travelers Day trip from Luxor to Ca...

Tour Location: Cairo...

Tour to Luxor West Bank For Indian Travelers Tour to Luxor West Bank is like steppin...

Tour Location: Luxor...

Tour to Edfu and Kom Ombo For Indian Travelers Edfu & Kom Ombo tour from Luxor w...

Tour Location: Edfu/Kom Ombo...

Trip to Dandara and Abydos from Luxor for Indian Travelers A Trip to Dandara and Aby...

Tour Location: Dandara/Abydos...

Hatshepsut’s temple itself was not fully destroyed, but many of its reliefs, statues, and inscriptions were intentionally defaced or removed after her death. This was largely due to her successor, Thutmose III, who sought to erase her legacy as a ruling female pharaoh, an unprecedented role in ancient Egypt that disrupted the traditional male line of succession.

Roughly 20 years after her death, Thutmose III ordered her images and names erased, possibly to reinforce the traditional idea that kingship should be male. Additionally, during the Amarna Period, pharaoh Akhenaten targeted images of Amun, Hatshepsut’s divine father, further damaging parts of her temple.

The combined impact of these acts led to the partial destruction of Hatshepsut’s temple, although much of it has been preserved and later restored by archaeologists.

Queen Hatshepsut was not buried in her temple at Deir el-Bahari. Although the mortuary temple was intended for her funerary rites and worship, her tomb was located in the Valley of the Kings. Her burial site, known as Tomb KV20, is situated deep within the cliffs nearby. KV20 is one of the oldest tombs in the Valley of the Kings and was originally prepared for her father, Thutmose I.

Hatshepsut later extended the tomb to accommodate her burial, intending for both her and her father to be honored together. Her mummy was eventually discovered in 2007, confirming her burial in the Valley of the Kings rather than in the temple.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut reflects public opinion in several key ways, particularly in how it was designed to establish and legitimize Hatshepsut’s rule. Through the temple’s elaborate reliefs and inscriptions, Hatshepsut presented herself as a divinely chosen ruler, portraying her birth as a result of the god Amun’s direct intervention.

The temple also depicted successful projects like the expedition to Punt, emphasizing her prosperity-focused, peaceful reign. These elements would have bolstered her public image by connecting her rule with both divine favor and tangible achievements.

The scale and grandeur of the temple itself also symbolized strength and legitimacy, appealing to the Egyptian reverence for continuity and order. Even after attempts to erase her memory, the temple’s grandeur ensured her story would endure, ultimately reflecting the impact of her rule on Egypt’s cultural memory.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut was built during Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty, a part of the New Kingdom period (1550-1070 BCE). This dynasty is known for some of Egypt’s most powerful rulers, such as Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and Akhenaten, as well as monumental building projects, flourishing trade, and military campaigns.

The Eighteenth Dynasty was particularly focused on consolidating wealth, power, and religious institutions, which is reflected in Hatshepsut’s temple and other grand structures of the time.

The path leading from Hatshepsut’s temple to the Valley of the Kings is commonly referred to as the causeway. This causeway connected the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut to her Valley Temple, a ceremonial route used for processions, particularly during the annual Beautiful Festival of the Valley.

This festival involved the movement of Amun’s barque from Karnak to the mortuary temples, where rituals honoring the dead pharaohs were performed. The causeway, symbolically and functionally, linked the temple to the Valley of the Kings, enhancing the temple’s role in funerary traditions and the journey of the soul.

The entire country of Egypt deserve to be explored with its every heavenly detail but there are places that must be seen before any other such as the breathtaking Hurghada's red sea, The wonders of Cairo the pyramids of Giza, the great sphinx, the Egyptian Museum, Khan El Khalili Bazaar, the wonders of Luxor like Valley of the Kings, Karnak & Hatshepsut temple and the wonders of Aswan such as Abu Simbel temples, Philea temple, Unfinished obelisk and The Wonders of Alexandria like Qaitbat Citadel, Pompey's Pillar and Alexandria Library. Read more about the best places to visit in Egypt.

If you want to apply for a Visa On Arrival that lasts for 30 days then you should be one of the eligible countries, have a valid passport with at least 6 months remaining and pay 25$ USD in cash, as for the E-Visa for 30 day you should have a valid passport for at least 8 months, complete the online application, pay the e-visa fee then print the e-visa to later be presented to the airport border guard. You could also be one of the lucky ones who can obtain a free visa for 90 days. Read more about Egypt travel visa.

Egypt has a variety of delicious cuisines but we recommend “Ful & Ta’meya (Fava Beans and Falafel)”, Mulukhiya, “Koshary”, a traditional Egyptian pasta dish, and Kebab & Kofta, the Egyptian traditional meat dish.

The best time to travel to Egypt is during the winter from September to April as the climate becomes a little tropical accompanied by a magical atmosphere of warm weather with a winter breeze. You will be notified in the week of your trip if the Climate is unsafe and if any changes have been made.

You should pack everything you could ever need in a small bag so you could move easily between your destinations.

We have been creating the finest vacations for more than 20 years around the most majestic destinations in Egypt. Our staff consists of the best operators, guides and drivers who dedicate all of their time & effort to make you have the perfect vacation. All of our tours are customized by Travel, Financial & Time consultants to fit your every possible need during your vacation. It doesn't go without saying that your safety and comfort are our main priority and all of our resources will be directed to provide the finest atmosphere until you return home.

You will feel safe in Egypt as the current atmosphere of the country is quite peaceful after the government took powerful measures like restructuring the entire tourist police to include all the important and tourist attractions in Egypt. Read more about is it safe to travel to Egypt.

Wear whatever feels right and comfortable. It is advised to wear something light and comfortable footwear like a closed-toe shoe to sustain the terrain of Egypt. Put on sun block during your time in Egypt in the summer to protect yourself from the sun.

The best activity is by far boarding a Nile Cruise between Luxor and Aswan or Vise Versa. Witness the beauty of Egypt from a hot balloon or a plane and try all the delicious Egyptian cuisines and drinks plus shopping in old Cairo. Explore the allure and wonders of the red sea in the magical city resorts of Egypt like Hurghada and many more by diving and snorkeling in the marine life or Hurghada. Behold the mesmerizing western desert by a safari trip under the heavenly Egyptian skies.

There are a lot of public holidays in Egypt too many to count either religious or nation, the most important festivals are the holy month of Ramadan which ends with Eid Al Fitr, Christmas and new years eve. Read more about festivals & publich holidays in Egypt.

Egypt is considered to be one of the most liberal Islamic countries but it has become a little bit conservative in the last couple of decades so it is advised to avoid showing your chest, shoulders or legs below the knees.

Arabic is the official language and Most Egyptians, who live in the cities, speak or understand English or at least some English words or phrases. Fewer Egyptians can speak French, Italian, Spanish, and German. Professional tour guides, who work in the tourism sector, are equipped to handle visitors who cannot speak Arabic and they will speak enough English and other languages to fulfill the needs of all our clients.

The fastest way is a car, of course, a taxi. If you are in Cairo ride a white taxi to move faster or you could board the fastest way of transportation in Egypt metro if the roads are in rush hour.

The temperature in Egypt ranges from 37c to 14 c. Summer in Egypt is somehow hot but sometimes it becomes cold at night and winter is cool and mild. The average of low temperatures vary from 9.5 °C in the wintertime to 23 °C in the summertime and the average high temperatures vary from 17 °C in the wintertime to 32 °C in the summertime. The temperature is moderate all along the coasts.

It is the home of everything a traveler might be looking for from amazing historical sites dating to more than 4000 years to enchanting city resorts & beaches. You will live the vacation you deserve as Egypt has everything you could possibly imagine.